Read through Bob Iger’s book, “The Ride of a Lifetime” and really enjoyed it. He’s a good storyteller, and a lot of his “leadership lessons” are things I want to have confirmed by someone of his stature, so … yeah, I liked it a lot.

One thing that struck me, though, is that Iger fairly deftly understood how streaming and other tech was going to disrupt Disney’s distribution channels. I don’t think he’s going to be CEO of Disney really long enough to ride the whole next wave, but I think whoever succeeds him will have to have a really good understanding of how much tech is about to change content creation.

I think we’re many years off from machine-written scripts – but what I think AI can do is essentially “Rapid prototype” entire movies, where you can stuff a script into it, and get some basic performances/visuals out quickly – like, faster, more detailed, moving storyboards. It won’t replicate the hand of a director, or the nuances of human actors (at least not yet), but I’d be very surprised if a lot of preproduction steps of films validate scripts and ideas by quickly turning them into like… “quick renders” of scripts that are largely done by machine.

And then you’d have a director essentially work with some folks to “tune” that quick render so it more closely matches their vision, and you’d invest time in specific sequences to flesh them out in more detail. But I expect you’ll get to a point where you can have a pretty phenomenal pre-vis of your movie by just using off the shelf tools.

Maybe the way tech will be disrupting content creation will be totally different. But that seems like a plausible path forward to me, and I think, again, that the best uses of tech/AI will be those that are *driven* by artists, and refined by artists.

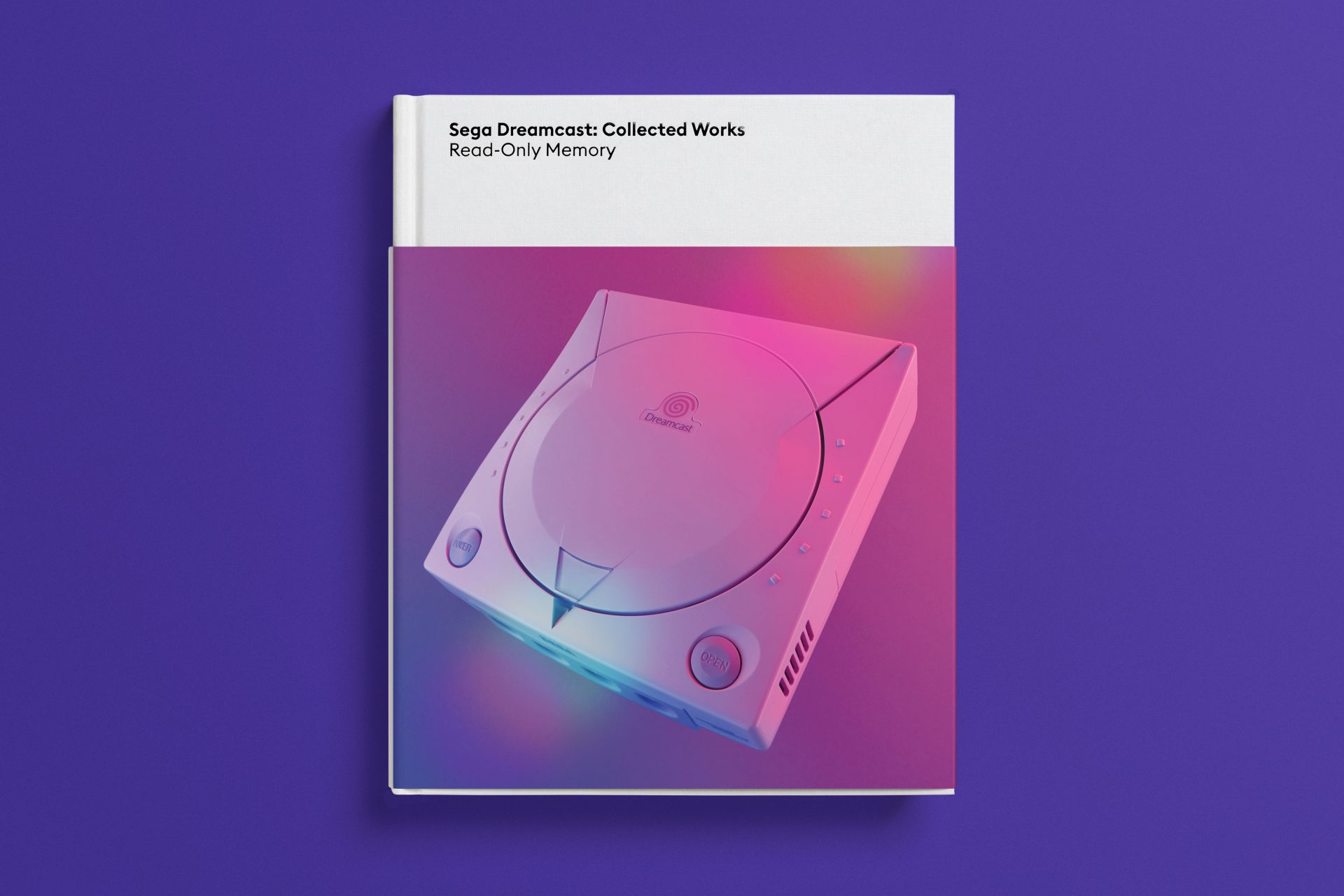

I picked up a book by

I picked up a book by